Having too many Domain Admin accounts weaponizes ordinary aspects of Active Directory that an attacker can use to take full control. Most write-ups simply stop at “remove extra admins” and “use MFA,” which is not enough. Listed below are the true, technical reasons a large or loose Domain Admin population degrades your security, low-level signs to look for, and exact steps you can take right now to address the cases others overlook.

The subtle attack paths that grow when the admin count rises

1. Shadow admins through ACLs

Particularly, an account does not need to be a member of Domain Admins to hold Domain Admin privileges. If a user is assigned specific permissions on the Domain Admins group object, or on domain objects using Access Control Entries (ACEs), the user will have access to perform administrative tasks without being visible as a current member of Domain Admins. Both security tools and attackers alike will look for those hidden ACEs to identify users who can perform administrative tasks at the domain controller.

Ensure that you review accounts with full control permissions on the domain objects that are important to your organization. If you simply examine group membership, administrators who “shadow” in your organization will also escape detection from the audit process for identity.)

2. DCSync and credential theft that bypasses passwords

An account that is permitted to replicate directory data may allow an adversary to request password hashes from a Domain Controller. As a result, the attack could be extracting NTLM hashes or Kerberos keys to build valid tickets. This is not an “admin logs in” event; it is an API call able to be made by any principal with replication rights. Finding accounts with the replication permissions is always helpful, and auditing any usage of Directory Replication Service calls can prove valuable.

3. KRBTGT compromise and Golden Ticket persistence.

If an attacker steals the krbtgt account hash, they can generate Kerberos tickets that are valid indefinitely. The only way to remove the forged ticket is by rotating the krbtgt keys, but this is a complicated process. It is something that has to be done carefully, usually at least twice, and if done incorrectly, can invalidate a cross-domain trust. If you have multiple server administrators, the risk of one of their credentials being compromised is more likely, and the chance that an attacker has forged several long-lived tickets is higher. Detection is difficult because forged tickets look perfectly normal for the most part to logging.

4. Service accounts acting as silent admins.

Service accounts are commonly given extensive rights for convenience, and their credentials aren’t changed and logged just as actively. In the scenario where a service account has delegated admin privileges, the account might not be associated with an interactive logon session, so it can act as a stealthy backdoor. When you look for accounts that have user attributes like “password never expires“, long account password age, zero recent logons, but are members of privileged groups, you have a target worth attacking.

5. Abuse of delegated rights and replication-style operations.

There are a few permissions that might not raise concerns but provide complete control when combined with others. A few examples: the ability to write the msDS-KeyCredentialLink attribute, to add SPNs, resource-based constrained delegation and control of certificate templates in AD CS. Any permissions above, when abused, can allow the attacker to impersonate other accounts, escalate or mint valid certificates that are trusted by Windows. An overexposed admin population raises the chances those bad actors are given bad rights.

6. Nested groups, vendor, and temporary accounts.

What you see in the Domain Admins list is only a small part of the issue. A single nested group inside Domain Admins can essentially promote dozens of its members. Vendor or contractor accounts added for a short job often remain on for months or even years. This temporary sprawl is one of the primary contributors to uncontrolled privilege growth. Microsoft’s guidance is explicit: review and deprecate membership.

7. Certificate services and AD CS abuse.

An adversary who can influence a certificate template or CA can issue certificates for any subject name, including domain controllers or users with elevated privileges. Those certificates are trusted in AD and can obtain content for which explicit credentials would normally have been required. Many teams do not restrict AD CS roles or monitor template edits. This attack vector scales when many administrators are able to edit templates. (Refer to vendor and research advisories on AD CS abuse.)

These are fast checks that can be run to reveal high priority risks and areas of focus.

- Accounts that have replication permissions or DCSync rights, granted somewhere outside of the default domain controller/container.

- Accounts that are not members of a group that has full control ACEs on Domain Admins, Enterprise Admins, or AdminSDHolder.

- krbtgt password age greater than 6 months and no evidence of a rotation plan.

- Service accounts that have a password that never flags and that are not recorded with a recent owner or service ticket.

- Nested groups that expand Domain Admins into a large set of users.

- Changes to certificate templates, a CA role change, or unexpected events in certificate issuance.

If you find any of these, take action immediately.

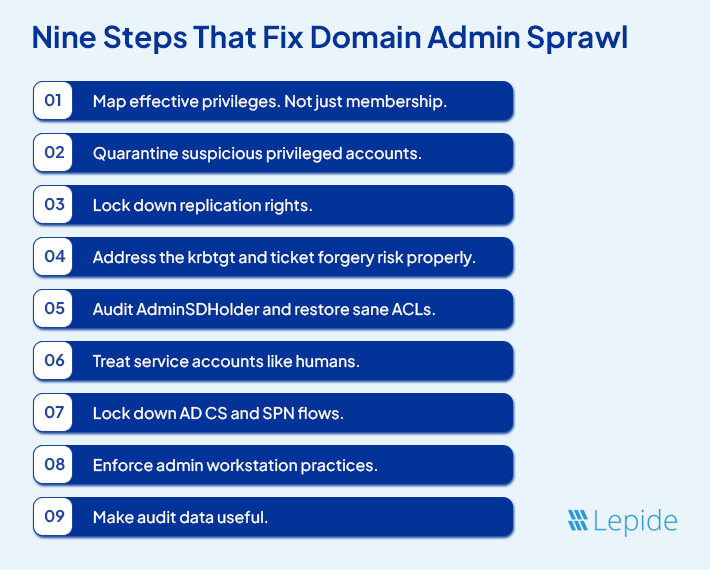

Exactly what to do, step by step. Not policy. Real actions.

These steps are ordered by impact and by safety. Do the top ones first. Each step is actionable and measurable.

- Map effective privileges. Not just membership– Perform a scan that returns every account that can act as a Domain Admin by any means available. This includes direct membership, nested membership, ACEs assigned full control, replication rights, and privileged attributes similar to, for example, Add-SPN or Write-DCSync, or control over AD CS template. Export this data. This is the baseline for your attack surface mapping. Use tools that indicate effective rights rather than just group memberships.

- Quarantine suspicious privileged accounts– For accounts you cannot justify, drop them into a holding OU with logon restrictions, so that they cannot be used to log on to production systems. Change their password and turn on forced MFA wherever possible so that they can be tagged for review by a user committee. Do not delete unless you have confirmation from the owner. Track every ability change in a tracking system. This purchase you time while conducting an investigation.

- Lock down replication rights– Remove replication and DC sync right from any user who does not need it. Verify only that DCs and replication-managed accounts managed by AD have those permissions. If you find that a non-DC account can call replication APIs, you should begin questioning who granted it those rights, when those rights were granted, and if there are any evidence that the account has been used.

- Address the krbtgt and ticket forgery risk properly– If there are questions regarding the security or obscurity of krbtgt credentials, two-step krbtgt password reset should be planned. The reset will require first to communicate the plans to the affected domain controllers and monitoring of the issuance of old tickets, recognizing cross-domain trusts and legacy services. If you are not clear, seek outside guidance. Absolutely do not blindly reset with no contingency plan.

- Audit AdminSDHolder and restore sane ACLs– AdminSDHolder grants a structure for protected accounts. If an attacker or past administrative action has introduced bad ACEs there, protected accounts will inherit bad rights. Compare AdminSDHolder ACLs to baseline defaults and remove inappropriate entries. Then, stop SDProp and revert to baseline AdminSDHolder ACLs.

- Treat service accounts like humans– Give the service account an owner. Rotate the password automatically. Alert when the account authenticates from a new place in the environment. Replace legacy service accounts with Managed Service Accounts or group-managed MSAs, where appropriate. Prevent privileged service accounts from interactive logons.

- Lock down AD CS and SPN flows– Review permissions for creating or modifying certificate templates and for issuing certificates. Require changes to be approved out of band. Audit SPN creation and utilize techniques like Kerberoast detection, since attackers regularly employ SPNs to request service tickets for the purpose of cracking service account keys.

- Enforce admin workstation practices– Require privileged operations to be performed on dedicated admin hosts. Prevent DA accounts from signing into desktop workstations and email clients. Use separate accounts for daily work and for privileged work. This mitigates the risk of phishing or commodity malware from being leveraged into a full domain compromise.

- Make audit data useful– Centralize log collection. Correlate: account added to a privileged group + new DCSync calls + suspicious certificate issuance = immediate incident indicator. Setup alert thresholds and utilize an enrichment pipeline to cross-reference an account to its owner, last password change, last interactive logon, and whether it is a service account. This makes every alert significant.

Recovery playbook for a suspected Domain Admin Compromise

If you think a Domain Admin account is compromised, complete these actions quickly and in order

- Disable the account, revoke trust tokens, and reset passwords on linked accounts.

- Revoke replication rights for the potentially compromised account from non-domain controllers or deny the account access to all hosts.

- Look for anomalies in the lifetimes of Kerberos tickets, unusual TGS requests, or avoidable krbtgt usage.

- If krbtgt appears to it may have been used, plan on performing a two-step reset.

- Revoke any certificates if you believe AD CS has been used to issue rogue certs

- Inventory ACLs and revoke any suspicious ACEs, especially entries that grant full control over privileged group objects.

- Restore from a known and trusted backup only when you are positively sure that the attacker has no reuse of their key or ticket. Otherwise, rebuild DCs and rotate secrets

How Lepide helps

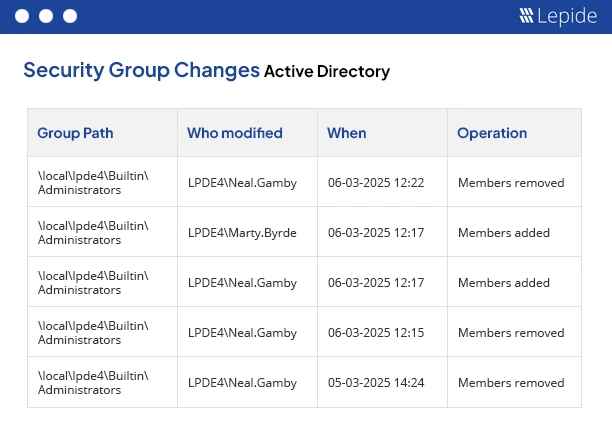

Lepide gives you clear, usable views of effective privilege. It shows direct and nested membership, and it highlights accounts that have admin-level ACEs even if they are not members of privileged groups. You get “state at time T” snapshots and a change history for group membership and ACL edits, which makes it possible to see who gave a permission, when, and why. This is exactly what you need to map shadow admins, service-account sprawl and nested group growth.

Lepide also sends real-time alerts for the high-risk events such as: additions to high-privilege groups, ACL changes on AdminSDHolder or Domain Admins, replication-permission grants, and AD CS template changes. Those alerts are enriched with context such as last logon, password age, and owner, which turns noise into actionable tickets. Use those alerts to enforce temporary admin expiry, trigger immediate quarantine, or kick off an incident response playbook.

Conclusion

Having too many Domain Admins is an operational risk. Attackers know that a good place to first attack is the Domain Admins. Errors by an admin can then cascade into full domain compromise. Service accounts and nested groups only compound this even further. The more endpoints you have using those domain-level admins, the more risk you create.

However, the story is not all bad. When you think this through and conduct a structured series of actions, inventorizing all members, rationalizing membership, monitoring for alerts, securing privileged account practices, and using a tool like Lepide to provide you relevant things to look for and enabling visibility and control over memberships, you will be changing that broad set of exposures to a managed process; from a state of uncertainty of “maybe secure” to “we are reducing risk.”

If you want to see how these risks look in your own environment, you can try Lepide Auditor yourself. Start a free trial or book a demo to walk through the data that matters.