The fastest way to cause serious harm to an Active Directory environment is to grant the right access to the wrong person. Every security team knows this while still being stuck with permission sprawl, ghost privileges, and nested group madness that no spreadsheet can resolve. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) in Active Directory is the only way to prevent access from growing faster than you can audit it.

This guide will demonstrate how to put role-based access control in place in Active Directory with simplicity and zero theory.

What are the common reasons RBAC fails in Active Directory?

Most teams understand what role-based access control is. The gap between design and reality is the problem. From what we have seen within actual environments, failure tends to show up in four different ways.

- Roles are copied from job titles instead of tasks. Job titles change frequently, and responsibilities change more slowly.

- Nested groups grow without ownership, where no one is clear on which group owns access to truth or what access path each group controls.

- The application teams ask for an exception instead of mapping requests to roles, and the exceptions begin to grow into a parallel permission model.

- There is no feedback loop to check that roles even map to reality, and without reviews, roles become the authentication mess they were meant to get rid of.

If you can avoid these four mistakes, the configuration becomes much easier and the model remains useful.

What are the steps to implement Role-Based Access Control in Active Directory?

The moment RBAC starts working is when you stop designing access around job titles and start designing it around repeatable tasks. Titles change often and mean different things across departments. Tasks stay stable and can be measured. When roles reflect tasks, you can test them, audit them, and prove they match reality. That is the insight most teams miss, and it is why RBAC fails more from design mistakes than technology limitations.

- Set clear goals first

- Collect current access information

- Define roles based on tasks, not job titles

- Use AGDLP to create the role structure

- Use clear naming + assign group owners

- Pilot on a small scope

- Migrate access slowly and safely

- Add controls to maintain RBAC

- Track the only metrics that matter

1. Set clear goals first

Focus on these four questions and write the answers down.

- What sensitive assets can only be accessed by documented roles?

- What elevated access is needed for specific tasks?

- What happens to roles when employees are onboarded or offboarded?

- How do you know if the role continues to reflect the reality of the business?

Measure your onboarding period, count the number of exceptions raised, and count the direct permissions discovered that are not in the role model. These will be your key performance indicators (KPIs).

2. Collect current access information

Don’t rely on your imagination. Instead, gather this information:

- Group membership directory and direct ACLs

- Interview app owners and operators

- Actual Usage logs that show what resources people use

Many teams neglect to gather usage logs, which is frequently a reason why their migrations fail. Usage logs help you identify which permissions are effective (currently in use) and which ones are unimportant (historical) and should be ignored in your migration plans. You sample 10 to 20 high-value resources, then analyze who can access them through effective permissions (what permissions they have in effect). This analysis will often reveal access paths that you would not have identified by solely looking at group names.

This is especially true in environments with nested groups. A user may appear to have minimal access based on group membership alone, but inherited permissions through nested groups or legacy ACLs may allow far more reach than expected. Understanding the current state prevents you from designing roles that look clean on paper but break critical workflows in practice.

3. Define roles based on tasks, not job titles

Name the functional role in one short phrase. E.g., “Finance: Account Manager”, “Support: AD Password Reset”, “Backup: File Server Recovery Operator”

Each role is the answer to the following two questions: What does the role allow me to do? Which data/system does this role access? Your answers should be one line for each question. Your answers must be verifiable. If your role(s) appear to be too broad, you may need to break the role(s) into multiple roles.

Your role(s) will be more beneficial to you if you separate them based upon responsibilities. If you have multiple roles where one grants access to customer data and the other grants access to billing data, consider separating the two so the blast radius of compromise is smaller and your auditing of both roles has a clearer correlation to accountability.

4. Use AGDLP to create the role structure

Implement roles through groups using the AGDLP model. AGDLP stands for Accounts > Global Groups > Domain Local Groups > Permissions. In practice, this means placing user accounts into Global Groups that represent roles in the business, nesting those Global Groups into Domain Local Groups that provide the resource permissions, and assigning permissions only to Domain Local Groups.

This structure provides a clear distinction between identity and permissions and creates an easy-to-read permissions map for auditing. It prevents you from assigning permissions directly to users, which is difficult to track and often forgotten over time. AGDLP also makes changes safer. If someone moves departments, you only need to adjust their group membership instead of hunting through individual ACLs on multiple systems. It is the approach Microsoft documents for native Active Directory domains. Follow it unless you have a very unusual topology.

5. Use clear naming + assign group owners

- Make names tell the story. Use this pattern:

- DL-File-Share-Read-Finance

- GG-Finance-Invoice-Approver

- Every group must have a human owner and a documented business reason. If the business reason disappears, the owner must remove the group or archive it. No owner, no group.

Ownership plus naming equals auditability. You will thank yourself when the auditor asks why someone has access.

6. Pilot on a small scope

Do not flip everything at once. Start with a single application or department and convert their existing permissions into a role-based model for that application/department. Pilot the role-based model on either the next business cycle or for at least thirty days.

During the pilot period, measure the following three metrics:

- The time taken to provision new users.

- The number of exceptions raised during the pilot period.

- The number of direct permissions that are not associated with the role-based model.

If there is a spike in exceptions raised, that means the role is incorrect; if the time to provision new users decreases and the number of exceptions decrease, it indicates that you are on the right track.

7. Migrate access slowly and safely

The initial state of the most shared folders in most environments is to provide users access to folders either from legacy access groups in shared folders created for past projects or through nested groups, which no one truly comprehends. To transition the access methods from their current form to a clean, role-based scheme is done through the migration process, without affecting how people currently work and using what today is considered best practice.

In order to successfully complete the migration, it is to be performed using a staggered approach, starting with groups that pose the least amount of risk or single departments. Users who perform the same work will be assigned to new Global Role Groups based on the role that they perform today, and the access granted to the Global Role Groups will be through Domain Local Groups with the existing access remaining in the transition to allow time to prove that the newly assigned role groups are legitimate. The use of this “shadow mode” will give the opportunity to prove that users will continue to have access to the systems they require to perform their job function, prior to taking away the existing permissions.

After all appropriate validations have been performed for the conversion to Global Role Groups and to confirm that the coverage provided is correct, a timetable for the gradual removal of all existing direct ACL entries and legacy access groups should be established. All changes to the access of any user should be performed using either a script or an automated process to ensure consistency and accuracy and to thus avoid human error. Human errors are where downtime occurs. Therefore, the overall goal of migrating users from the current access method or historical access methods to the structured access based on the Global Role Groups, while at the same time, not disrupting their ability to perform their jobs daily, should remain the same.

8. Add controls to maintain RBAC

RBAC is an operating model, not a project. The necessary controls include:

- Quarterly Role Reviews for Privileged Roles

- Semi-Annual Functional Role Reviews

- Automated Alerts for Resources With Direct Permissions That Should Only Be Changed via Role Assignment;

- A Process to Grant Temporary Elevated Access with Automatic Expiry of Access.

Failure to automate the expiry process for temporary access results in permanent exceptions.

9. Track the only metrics that matter

Vanity Numbers are Not Suitable for Tracking Purposes. Rather:

- Track the Percentage of Permissions Assigned through Role Groups vs Directly to Users

- Track the Number of Exceptions Per 1000 Users Counted per Month

- Track the Volume of Inactive Accounts with Active Permissions

These metrics reflect the viability of your model. If the Percentage of Direct Assignments Increases, the Model is Failing.

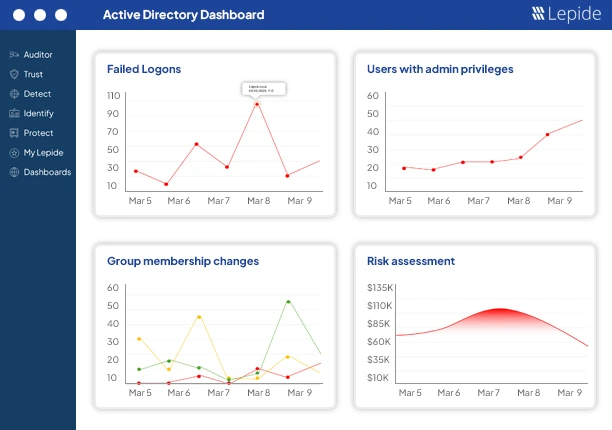

How Lepide helps

Lepide Auditor for Active Directory gives you clear visibility into access across Active Directory so you can verify that your role-based access control model matches reality. It shows effective permissions through nested groups and inherited ACLs, which removes the guesswork that usually slows down pilots and migrations. During rollout, you can confirm that users only have access through role groups and spot any direct permissions that would break the model before they become a problem. This matters because you cannot fix what you cannot see, and most RBAC failures come from blind spots rather than design.

After deployment, Lepide helps you keep the model clean. It alerts you when someone adds a user to a sensitive group or assigns access outside the RBAC structure. It also provides reports that explain who has access, when it was granted, and the change history linked to that access. This reduces audit time and prevents the gradual decay that typically kills RBAC programs within a year. Instead of rebuilding the model again in two years, you maintain it with proof and accountability. You can try Lepide for free by downloading the free trial or schedule a demo with the team.

Conclusion

Role-based access control in Active Directory stops permission chaos by tying access to what people actually do. Define roles based on the tasks performed, adopt roles based on the group structure, understand effective permissions before migration, and verify on an ongoing basis. Use tools that identify nested paths and historic changes to evidence that the model is effective. By doing what is described, you limit the likelihood that the wrong person has the right access, making it a preventable problem instead of one you discover after the fact.