Poorly designed password policies are not just an irritation to IT, . they create an operational weakness that attackers can exploit before your fancy controls ever come into play. When policy encourages people to behave predictably, attackers thrive

Where does conventional password policy fail?

1. Complexity without context creates predictable shortcuts

Organizations often handle credential risk through increased complexity (i.e., special characters, history rules) and calendar-based rotation. On the surface, this sounds reasonable, but humans have limited memory and incentive. When dealing with overly complicated rules, employees often take predictable shortcuts: they reuse, create patterned variations (e.g., Spring2025! -> Summer2025!), or store them in an insecure location. And those patterns are exactly what automated attacks thrive on.

When patterns are encoded as secrets by millions of employees with low entropy through numerous automated attacks, these secrets become easier to guess or crack, as attackers conduct wide and strategic automated runs against public corporate-facing services.

2. Rotation on schedule creates predictability, not safety

The standard “change between 60 and 90 days” policy was initially implemented when brute-force attacks were significantly different and the amount of leaks was much smaller. Currently, some indications and recommendations support changing a password based on a security event (compromise, detection) rather than doing it at a regular time interval. Scheduled password changes result in more helpdesk calls, greater user dissatisfaction, and the trend of using weak patterned changes, which are risk factors that occur downstream. (NIST guidelines are in favour of targeted rotation processes rather than unplanned resets.)

3. Dormant and service accounts are the forgotten doors

Password policy discussions mostly revolve around end users, whereas service principals, vendor accounts, and inactive AD accounts function outside the strict password rules. End-user accounts are often long-lived, under-monitored, and sometimes, they are even privileged. Attackers search for these very “quiet” accounts because they make very little noise and have a very high impact once compromised.

People don’t fail security; policies do

Security professionals typically view user behavior, also commonly referred to as human factors, as a problem to be solved via additional policy rules. This is a dangerous misconception. Human behavior is predictable; therefore, policy should be based on that predictability.

Here are the three realities of psychology that you need to accept right now:

- Memory is constrained. The more unique secrets you require users to have, the more likely the human factor will either reuse secrets or document them in some way.

- Burden is the same as circumvention. Every additional friction point will move users toward the path of least resistance.

- Risk is local. Users do not have the visibility to be able to appreciate enterprise-level risk. Users will make decisions based on minimizing their individual friction point, not perceived aggregate organizational risk.

In other words, people will comply with policy as long as it aligns with human cognition. When it does not align, people will invent compensations like incremental changes (add !1), reusing across systems, or storing credentials in an insecure document

How Hackers Beat “Good” Passwords

1. Password Spraying That Uses Your Own Rules Against You

Hackers have shifted from attempting a million passwords on a single account. This is obvious and makes the alerts go off. Today, hackers will simply try one clever password across a million accounts.

That clever password is based on your company’s pattern for passwords. If you work at “XYZ Organization” and enforce password changes quarterly, hackers will try:

- XYZOrganization2025!

- XYZ2025!

- Welcome2025!

- Password2025!

If there are 10,000 employee accounts to access, even a 2% success rate will give hackers more than 200 ways in.

2. Using Stolen Passwords from Other Websites

People reuse passwords. Even when they know better. Even after training.

When a shopping website or streaming service gets hacked (and billions of passwords are now available on the dark web), attackers test those passwords on business systems. Your employee’s Netflix password might be close enough to their work password that simple changes crack it.

3. Tricking the Help Desk

Here’s an attack your password rules accidentally enable: When forced password changes frustrate people so much that password resets become normal, your help desk becomes a weak point.

Attackers call pretending to be employees who forgot their password (again). The help desk gets so many legitimate reset requests because of your complex rules that they become less careful about checking who’s really calling. One successful reset gives the attacker access to your network.

4. Going After Privileged Accounts

The most dangerous password problems aren’t in typical employee accounts; they’re in admin accounts that operate with extra privileges.

Yet, the majority of organizations apply the same fundamental password guidelines for everyone. As a result, a system account that requires stable passwords for automation gets locked out because someone used the same quarterly change rule for that account as well. This requires the IT team to make an exception or to use a simple password to prevent the lockout itself.

So, what should password rules look like in 2025?

Stop designing rules for just auditors. Start designing them for attackers and employees, too

Rule 1: Length Beats Complexity

The surprising truth is that a password, like “correct-horse-battery-staple”, is more secure than “P@ssw0rd1!”

Why? Because password security actually relates to length and randomness, not a mix of characters. Derived from common words, a 25-character-long passphrase will be harder to hack than a 12-character-long “complex” password that uses the predictable character swaps of ‘P@ssw0rd!’ or ‘Tr0ub4dor&3’ and violates obvious patterns.

Better password policies should therefore:

- Require 15 characters or longer (20+ for administrative accounts)

- Encourage phrases instead of passwords

- Eliminate random complexity requirements that don’t provide real security

- Enable the use of spaces and longer passwords

Rule 2: Stop Forcing Regular Password Changes

Do not force people to change a password unless there is evidence that it has been compromised. Security experts are unequivocally clear on this; you don’t need to force change if it has simply been a period of time.

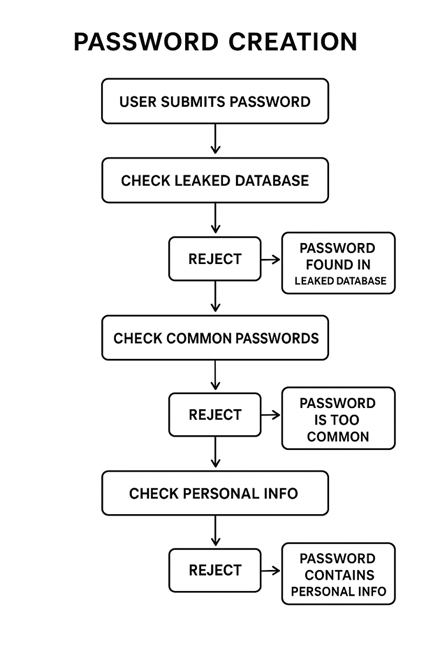

If you want to require a password change, you should:

- Be aware of compromised passwords by checking the leaked password database

- Only require a change when there are indications that there is a sign of compromise

- Observe accounts for unusual attempts to sign in

This limits fatigue with password changes, stops patterns from emerging, and focuses attention on security on actual system bad actors.

Rule 3: Add Two-Factor Authentication

Implementing two-factor authentication is a way to really beef up security, since even if a hacker captures your password, they can’t get into your system without the second factor.

Not all second factors are created equal:

- Text messaging codes (can be intercepted)

- App-based codes (can be phished)

- Hardware keys (the strongest, but least convenient)

- Fingerprints (can be pretty convenient, depending on how they are configured)

The smart move is to match the factor to the risk, for example, using app codes for a normal login, but requiring a stronger factor for admin access or for logging in from some unusual location.

Rule 4: Block Known Bad Passwords

Instead of generic rules against certain characters, check against

- Lists of known leaked passwords

- Databases of commonly used passwords

- Your company name and department names

- Any piece of personal information (names, birthdays)

- Any previously used passwords

This approach does not allow obviously weak passwords, but does allow users to create strong password phrases that may technically break the traditional rules.

Rule 5: Different Rules for Different Accounts

Not all accounts need the same protection; for example, a read-only account will need very different security than an administrator account.

Make tiers:

- Regular users – long phrases, second factor for remote work, inessential repetitive changes

- Administrator accounts – longer phrases (if feasible), always need a second factor, management tools (like password managers)

- System accounts – managed passwords, auto rotation, no human access

Rule 6: Make Security Easy

The greatest password failure is that secure options are more complex than insecure ones. If your secure option has a higher friction count, people will look for alternative options; therefore, make security convenient:

- Everyone gets a password manager (not optional)

- Single sign-on, so fewer passwords needed

- Passwordless option when possible

- Respond clearly to password strength, not just “weak”, but you may want a “longer phrase” or “fewer words”.

Watching for Attacks: The Other Half

No matter how good your password policy is, it can’t stop it all. You must also guard against attacks. Here’s what you need to guard against:

| Activity | Common Attack Signs |

|---|---|

| Login Problems |

|

| Account Changes |

|

| Unusual User Behavior |

|

The goal here is simply to join the dots together. One odd login might be acceptable. However, if there are several odd things across a couple of accounts at the same time, things are likely not as they appear, which is an attack.

How Lepide Helps

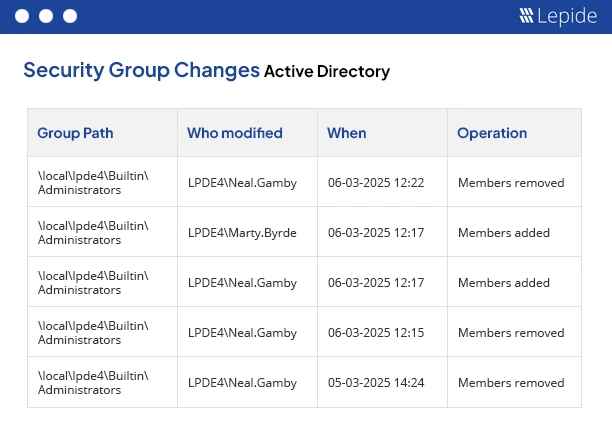

The Lepide Active Directory Security solution provides you with ongoing visibility into AD through auditing of changes, detection of suspicious activity, and identification of risky accounts based on configuration, privilege levels, or inactivity. It indicates where permissions are more than necessary, where there are accounts that do not ideally follow password and access practices, and alerts you to changes in policy-driven settings. For example, when a user receives higher privileged accounts, or a new account is created without appropriate leveling of privileges.

Lepide Active Directory Auditor captures detailed change events in AD. It logs who made what change when, including changes to password settings, group membership, account inactivity, password expiry settings, and whether accounts are set never to expire. It produces reports that show the status of these settings over time, allowing you to see any drift from your intended policy. Audit logs and alerting enable you to see when policy-relevant settings are changed and to act. It also supports rollback of unwanted changes.

If you want to discover how you can audit, detect, and secure your Active Directory before risks turn into breaches, download the free trial or schedule a demo with one of our engineers today.

Conclusion

Companies that execute password security correctly in 2025 know three things:

First, password policies are about human behavior, not merely technical rules. If your policy confronts how humans think, they will work around the policy, and attackers will work to use those workflows.

Second, being compliant and being secure are not the same thing. A policy compliant with audits that teaches users to create predictable passwords is not protecting you, except for your compliance score.

Third, password security isn’t about having the most complex requirements; password security is about having the proper requirements, proper monitoring, and a proper culture.

Unfortunately, the cold, hard truth is, if you can honestly say your password policy hasn’t been completely overhauled in the past three years, it is probably doing more harm than good.

Ask yourself three questions:

- If someone gained the password of one of your employees today, what’s stopping them from logging into your systems?

- Are your password requirements resulting in predictable patterns?

- Can you detect compromised passwords before they’re used?

If you cannot confidently provide a positive response to all three questions, your password policy is not protecting you. It is providing the facade of security while keeping your door wide open.

The best time to fix this was three years ago. The second-best time is now, before the next breach forces your hand.

FAQs

Q: Why are long passphrases better than complex short passwords?

Longer passphrases are easy to remember and more difficult for an attacker to guess. Instead of randomly forcing the inclusion of symbols and numbers, using a 15+ character phrase with personal meaning will increase security. Even if an attacker has some familiarity with common phrases, they will find it difficult to crack a long, unique phrase.

Q: How often should I change my password in 2025?

A password should be changed if there is an obvious indication of compromise. Changing passwords frequently creates a normal pattern that is predictable and frustrating for users. Monitoring for suspicious activity is a more effective course of action than requiring password changes at regular intervals based on a calendar.

Q: Can MFA fully protect against stolen passwords?

Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) provides an added level of security that is strong, but not perfect. App-based or hardware MFA keys are stronger than SMS codes. Using MFA for all admin accounts and remote access will significantly reduce the chances of someone getting in without authorization, even if the password is stolen.

Q: What risks do dormant or service accounts pose?

Inactive accounts, old service accounts, and vendor accounts often fall off the radar. These accounts may have elevated privileges for their age, and sometimes have little to no monitoring on them. Attackers target these types of accounts because they are able to silently access critical systems without alerting others.